Archive

Stories of Passion and Pinot

An important note: Stories of Passion and Pinot is a series that was started in 2016 and it keeps updating year after year with new stories. This post will serve as the starting page for the series and will be constantly updated as new stories are added…

It is easy to declare this grape a king. It is a lot more difficult to have people agree to and support such a designation. And here I am, proclaiming Pinot Noir worthy of the kingship, despite the fact that this title is typically associated with Barolo (made from Nebbiolo grape) or Cabernet Sauvignon.

Barolo might be a king, why not – but its production is confined strictly to Italy, and can be considered minuscule in terms of volume. Cabernet Sauvignon is commanding attention everywhere – but I would argue that it is more because of the ease of appeal to the consumer and thus an opportunity to attach more dollar signs to the respective sticker. Don’t get me wrong – I love good Cabernet Sauvignon as much or more than anyone else, but having gone through so many lifeless editions, I developed a healthy dose of skepticism in relation to this noble grape.

Talking about Pinot Noir, I’m not afraid to again proclaim it a king. If anything, it is the king of passion. Hard to grow – finicky grape, subject to Mother Nature tantrums, prone to cloning, susceptible to grape diseases – and nevertheless passionately embraced by winemakers around the world refusing to grow anything else but this one single grape – a year in, year out.

Historically, Pinot Noir was associated with Burgundy – where the love of the capricious grape originated, and where all the old glory started. Slowly but surely, Pinot Noir spread out in the world, reaching the USA, New Zealand, Australia, Chile, and Argentina – and even Germany, Italy, Spain, Canada, and South Africa are included in this list. Looking at the USA, while the grape started in California, it then made it into Oregon, and now started showing along the East Coast, particularly in Hudson Valley.

I don’t know what makes winemakers so passionate about Pinot Noir. For one, it might be the grape’s affinity to terroir. Soil almost always shines through in Pinot Noir – it is no wonder that Burgundians treasure their soil like gold, not letting a single rock escape its place. While soil is a foundation of the Pinot Noir wines, the weather would actually define the vintage – Pinot Noir is not a grape easily amended in the winery. But when everything works, the pleasures of a good glass of Pinot might be simply unmatched.

However important, terroir alone can’t be “it”. Maybe some people are simply born to be Pinot Noir winemakers? Or maybe this finicky grape has some special magical powers? Same as you, I can’t answer this. But – maybe we shouldn’t guess and simply ask the winemakers?

Willamette Valley in Oregon is truly a special place when it comes to the Pinot Noir. Similar to the Burgundy, Pinot Noir is “it” – the main grape Oregon is known for. It is all in the terroir; the soil is equally precious, and the weather would make the vintage or break it. And passion runs very strong – many people who make Pinot Noir in Oregon are absolutely certain that Oregon is the only place, and Pinot Noir is the only grape. I’m telling you, it is one wicked grape we are talking about.

I see your raised eyebrow and mouse pointer heading towards that little “x”, as you are tired of all the Pinot Noir mysticism I’m trying to entangle you in. But let me ask for a few more minutes of your time – and not even today, but over the next few weeks.

You see, I was lucky enough to have a conversation (albeit virtual) with a few people who combined Pinot and Passion in Oregon, and can’t see it any other way. What you will hear might surprise you, or maybe it will excite you enough to crave a glass of Oregon Pinot Noir right this second, so before you hear from a pioneer, a farmer, a NASA scientist, and a few other passionate folks, do yourself a favor – make sure you have that Pinot bottle ready. Here are the people you will hear from:

- Ken Wright of Ken Wright Cellars

- David Nemarnik of Alloro Vineyard

- Mike Bayliss of Ghost Hill Cellars

- Wayne Bailey of Youngberg Hill Vineyards

- Steve Lutz of Lenné Estate

- Don Hagge of Vidon Vineyard

I would like to extend a special note of gratitude to Carl Giavanti of Carl Giavanti Consulting, a wine marketing and PR firm, who was very instrumental in making all these interviews possible.

As I publish the posts, I will link them forward (one of the pleasures and advantages of blogging), so at the end of the day, this will be a complete series of stories. And with this – raise a glass of Pinot Noir – and may the Passion be with you. Cheers!

2017 – 2020 Updates:

This Passion and Pinot Series continues to live on. Here is what had been added during these 4 years – and you should expect to see more stories as we continue talking with the winemakers who made Pinot Noir their passion:

- Page Knudsen of Knudsen Cellars

- Tony Rynders of Tendril Cellars

- Dave Specter of Bells Up Winery

- Richard Boyles of Iris Vineyards

- Tom Mortimer of Le Cadeau Vieyard

- Dan Warnshuis of Utopia Vineyard

2021 Updates:

2021 was a good year as I added one more “Passion and Pinot” interview and also met in person with a number of winemakers I only spoke with virtually before – and this resulted in Passion and Pinot Updates.

New interview:

Passion and Pinot Updates:

P.S. Here are the links to the websites for the wineries profiled in this series:

Alloro Vineyard

Battle Creek Cellars

Bells Up Winery

Ghost Hill Cellars

Iris Vineyards

Ken Wright Cellars

Knudsen Vineyards

Le Cadeau Vineyard

Lenné Estate

Tendril Cellars

Vidon Vineyard

Utopia Vineyard

Youngberg Hill Vineyards

One On One With Winemaker: Michel Rolland

To anyone inside of the wine circles, the name “Michel Rolland” needs no introduction. If you enjoy an occasional glass of wine but don’t dig deep, very deep into what is behind the label, it will probably tell you nothing. Unlike Araujo, Bryant Family, Harlan, Staglin – right? All of these are the cult wines from California, revered, adored and drooled upon by many wine connoisseurs. Let’s not forget Tenuta dell’Ornellaia from Italy, Angélus and Ausone from St-Emilion and l’Evangile from Pomerol. In case you didn’t know, Michel Rolland, classically trained French winemaker, is behind these and hundreds (I’m not exaggerating – search for his name on Wikipedia) of other wines. He is a consulting winemaker, sometimes also referred to as “flying winemaker”, who made wine on all continents and all possible and impossible corners of the world.

When I got an invitation for lunch with Michel Rolland, who was visiting New York to introduce some of his newest wines, I was excited at first, and then bummed. The lunch was overlapping with the Jura wine tasting, which I was planning to attend for a very long time. So as a last resort, I asked if I can meet with Michel Rolland after the lunch so I can ask him a few questions. To my absolute delight, kind folks at Deutsch Family, a wine importer company hosting the event, managed to arrange the time for me right after the lunch to sit down and talk to Michel Rolland.

As you understand by now, unlike most of my virtual interviews in this “one on one” series, this was a real face to face conversation, with a real handshake and visible emotions. At first, I was thinking about recording our conversation. That probably would be okay, but I never did this before, and fighting with technology in front of the busy man who was doing me a favor didn’t feel right. So I did what I always do – I prepared my questions in advance. After a subway ride and a brisk walk, I arrived – on time – and shake hands with the legend. We sat at the table, three different glasses of red wine appeared on the table. And conversation started – here is what we were talking about, with the precision of my fingers hitting the screen of the trusted iPad:

Q1: You made wine all over the world. Is there one place or one wine which was your absolute favorite?

“No. I like the challenge, so every time I’m going to the new place, it is very exciting.”

Q2: What was your most difficult project and why?

“To make wine, we need soil, grapes, and weather. When the weather is not playing, it is very difficult. There were 2 places which were the most difficult. First one was India – everything is great except the climate. India has only 2 seasons – dry and wet. Another one was China – extreme climate, very difficult to make wines. In the project in China, years 1,2 and 3 had no frost, then in the year 4 we decided not to cover the vines, and half of the vineyard became dead.”

Q3: You are known to create big and bold style wines. At the same time, it seems that wines with restrained are more popular today. Did you make any changes to your winemaking style to yield to the popular demand?

“After 43 years in this job, it is good that I have style. So the style is what the market is asking – the wines are made to be sold, so we have to follow tendencies in the market. Even that not everything is changed at the same time, it is more of the evolution and adhering to the fashion. The wine to drink tonight is not the one to be stored for 10–15 years. So the wine have to be made more enjoyable younger, and this is what we do.”

Q4: Where there any projects which you rejected and if yes, why?

“Yes, of course, but it doesn’t happen very often. The biggest concern is the relationship with the team. Day to day in the cellar and field it is the team – if the relationship with the team is not good, I prefer to leave. For sure if nobody is happy, then it is better to leave. I never refused project because it is too challenging. In Chile, 25 years ago the variety called Sauvignonne had to be used, which was hard – and I didn’t refuse the project because it was challenging. So the relationship is the major part.”

Q5: Again, appealing to your worldwide expertise, what do you think is the hottest new wine region today, if there is one?

“We have to look back – we have new world and old world. France, Italy, Spain – being there before. Then came US, then South America. Chile, and Argentina is growing the fastest now. Then there is New Zealand and Australia. But I think the area around the Black Sea, which was historically there, is very promising. Now Turkey, Georgia, Armenia, Russia all started making really good wines and we will see great wines coming from there. I [actually] currently work in Turkey, Russia, Bulgaria.”

Q6: What are the most undervalued wine regions in the world today, if there are any left?

“One of the most difficult countries to make and produce wines is South Africa – great wines which sell well only in UK, but very difficult everywhere else.”

Q7: What do you think of natural wines, which are very often are very opposite in style to “big and bold”

“We can’t fight against natural wines, but all the wines are natural [laughing], minimal intervention. We have to slow down with all the chemicals, but the wines should be made to be good wines – a lot of “Bio” is done only for marketing, so if it is done smart, it is good. I have small estate Val de Flores in Argentina which is for 8 years is completely “bio”, so yes, I support that.”

Q8: What are the latest projects you are working on?

“The one in Tuscany (Maremma) running by the German family, they have a wonderful vineyard and wonderful winery, and now making very good wines.”

Q9: You are a role model and a teacher for many in the wine world. Who were your role models and teachers?

“When I began my job my mentor was Émile Peynaud. It was another era. When I began the oenology, we were not speaking about quality. The goal was to avoid problems. I discussed this a lot with Peynaud. Peynaud was convincing people to do better in the cellar, to have clean wines, to use better material. It was very difficult, but Peynaud was great dealing with the people, so I learned a lot from him, including the patience for dealing with people. I often said that my job is 80% psychology, and 20% oenology, this is what I learned from Peynaud.”

Q10: What are the new trends in the wine world? What wine consumers should expect to see and experience over the next few years?

“I think people like more and more approachable, and gentle wines – full bodied, but gentle. The big problem I see is that during the 90s, I did a lot of work where we dramatically improved quality. In the 2000s, we drunk best wines we could. What I don’t like now that everybody is going after cheaper and cheaper wines – we can still do good wines, but not better than in the previous years. In the end, the wine is a business, so I don’t want to see people reduce quality just to survive.”

As you can imagine, Michel Rolland didn’t come to the New York to talk to me. He was promoting his latest project, the wines of André Lurton which he helped to create. André Lurton is the winemaker in Bordeaux whose family winemaking heritage goes back more than 200 years, and who is not only known as a winemaker but also was very instrumental in advancing Bordeaux wine industry, including creating of the new appellations.

As you can imagine, Michel Rolland didn’t come to the New York to talk to me. He was promoting his latest project, the wines of André Lurton which he helped to create. André Lurton is the winemaker in Bordeaux whose family winemaking heritage goes back more than 200 years, and who is not only known as a winemaker but also was very instrumental in advancing Bordeaux wine industry, including creating of the new appellations.

Here is the story of how Michel Rolland started working with André Lurton (don’t you love wines with the story?):

“Lurton is one of the last projects. I had an interview on the radio, and the journalist asked me if I have any regrets. I said at 65 years old, I don’t have a lot of regrets. When making wines, you get to meet wonderful people from all over the world. So the regret is “why I never met this guy” – one of such people is André Tchelistcheff – I met his wife, but never met him. And then the journalist asked me “who else”. So I said in Bordeaux, there is André Lurton, who I never met and worked together.

3 hours after the interview I received a call from Andre Lurton who said: “come and meet me”. Now we are working together.

So what we are doing is looking after the future, what can we produce for the people. We have to make approachable wines – still with the ability to age, but more approachable. “

This was the end of my conversation with Michel Rolland. We spoke for about 45 minutes, and it was clear that Michel had to continue on with his day. But there were still three wines standing in front of me, so I had to go through the speed tasting and only capture general impressions, there was no time for detailed notes. Here are my brief notes:

2012 Château Bonnet Réserve Rouge Bordeaux ($14.99, Merlot/Cabernet Sauvignon blend) – beautiful tobacco nose, fresh fruit, soft, round – clearly Bordeaux on the palate, green notes, restrained. Green notes do get in the way, though.

2012 Château de Rochemorin Rouge Pessac-Léognan ($33.99, Cabernet Sauvignon/Merlot blend) – beautiful, classic Bordeaux, great finish, some presence of the green notes

2012 Château La Louviére Rouge Pessac-Léognan ($74.99, Cabernet Sauvignon/Merlot/Petite Verdot), new oak, open fruit on the nose, lots of complexity, very beautiful, layers, delicious finish. Overall delicious wine, my favorite of the tasting. This wine was polished and concentrated, and I would love to drink it every day.

What is interesting for me here (besides the clear proof that I’m a wine snob who prefers expensive wines) is that there is a clear progression of taste and pleasure in this three wines – the price was increasing accordingly, and this is how things are quite often in the wine world.

After an encounter like this one, and the pleasure of talking with the legend, if blogging would be my job, I would gladly proclaim “I love my job”. But even without it, I still would proudly say that I love blogging as it makes possible conversations like this one, which is priceless for any oenophile. Cheers!

Fire, Water, Air, Earth

Fire, Water, Air, Earth. Four basic elements, which uphold humankind. Literally and figuratively.

“When we learned to cook, we became fully human”.

When it comes to social media, which at this point we learned we can’t live without, the typical experience may be best expressed with one word – bombardment. During the day (more often than not, even during the night, so we might as well speak about 24 hours) we are bombarded with [probably] thousands of snippets, bit and pieces of “important” (can you imagine: mere 12 years ago, there was no social media as we know it – horror!) information – read this, watch that, listen to this. It is amazing that our brain can extract any interesting information while been under such a constant attack.

Talking about interesting – few weeks ago, I came across (don’t ask me where and how, the brain will not give up its secrets) a little article (I think) which also pointed to the video. The video happened to be a trailer for Cooked, the original Netflix documentary:

Two minutes of the trailer was enough for me to say I. Must. Watch it. Note that in general, I’m not a big fan of documentaries. But this trailer promised the movie done so well that I literally wanted to drop everything I was doing and start watching it.

I managed to contain myself until the evening. I also avoided binge watching (despite strong desire), and extended the pleasure over a few evenings.

Cooked is a documentary consisting of 4 episodes, called Fire, Water, Air and Earth, where award-winning author, Michael Pollan, looks at the history of cooking, what it means to humankind, and where it is today. Each episode is dedicated to one of the basic cooking elements – what we cook with fire, which was historically the very first cooking method; how water changes the way we cook; where do you see air come to play (spoiler alert: this episode is mostly about the bread), and then the earth, which is all about fermentation – did you know that about 30% of the food we eat every day is fermented? By the way, a mini quiz for you – do you know how chocolate is related to fermentation?

This series is all about honest, get back to your roots cooking. It is also about respect. Respect to the people, respect to the food we eat and its basic ingredients, whether it is meat, grains, cheese or anything else (gluten included – watch Nathan Myhrvold talk about science of gluten). Photography is incredible, with stunning images, and the whole series is just something you want to watch. And then watch again, as it really appeals to your very basic senses.

I don’t want to tell you anything else about the movie, except to [strongly] suggest that you should to go and watch it. Find a comfy spot, pour yourself a glass of wine, and indulge in something which is masterfully done, beautiful and thought provoking. And then may be dig up some of your mom’s recipes – and get cooking.

What Is A Good Wine?

Let’s say you are given a glass of wine. Can you tell if this is a good wine or not? Before you will jump on the obvious, let me clarify this question a bit – the wine is in the perfect condition – it is not corked, it is not cooked, it is not oxidized – there are no common faults of any kind, this is just a well made bottle of wine. So, is it good or not?

Let’s say you are given a glass of wine. Can you tell if this is a good wine or not? Before you will jump on the obvious, let me clarify this question a bit – the wine is in the perfect condition – it is not corked, it is not cooked, it is not oxidized – there are no common faults of any kind, this is just a well made bottle of wine. So, is it good or not?

Is this question even makes sense? Can such a question be answered? Let’s talk about something more common first – food. Imagine you are in a restaurant for dinner, with friends and family. The dishes start arriving, and here is a side of french fries. There is a very good chance that if the fries are executed properly – good color, nice consistent cut, crispy and not soggy, with the right amount of salt, tasting fresh – everybody at the table would universally agree that “the fries are good”, and you can only hope that there were enough fries ordered for everybody to share. What also important here is that nobody would be shy to slam these very french fries if something is not up to snuff – too much salt, fried in the old oil etc – everybody is confident in their ability to judge french fries to be universally good and tasty, or not.

Stepping up from the side dish, let’s take a look at the main dishes ordered around the table. Someone got steak, someone got lobster, someone is enjoying vegetarian lasagna. Now, it would be much harder to build taste consensus around the table for all these dishes. One person likes steak rare, and the other one only eats it well done – it will be very hard for these two to agree what is good and what is not. Someone might be allergic to a shellfish – there is no way they can even touch the sauce from that lobster dish to attest to your “this is sooo good” claim. So yes, it is hard to build a consensus here, but people are confident in their own right about the dishes they ordered to be able to judge good or not. If steak doesn’t have the right level of doneness, it will be sent back. If lobster is not seasoned right – well, not sure about “sent back”, but I’m sure the problem with the dish will be stated and discussed at the table. And of course if one states that their dish is delicious, then the whole table must try at least a tiny bit to experience “the goodness” (at least this is how it works in our family).

Now, arriving at a wine, the situation is different, and often dramatically. Unlike french fries, the wine still has an aura of mystery, of a special knowledge required to be able to understand and appreciate it, and to claim if it is good or not. The same people who are very confident to send underdone or overly salty (to their personal taste!) steak back to the kitchen, will be very shy and even afraid to say anything if the wine is obviously corked – they will take it as their own inability to properly understand the wine, and therefore will not say anything. Of course the situation is not as consistently dramatic as I present it here – wine today is very popular, and increasing number of people feeling confident enough around it to state what they like and not; however, step out of the oenophile circle, and go dine with people who drink wine occasionally, and I guarantee you will hear “ahh, I don’t know anything about wine” as an answer to the question if they like the wine or not.

In reality, making a personal “good/not good” decision about the wine is as easy as in the case of french fries. I took the “Windows on the World” wine school back in the day, which was taught by Kevin Zraly – Kevin is single-handedly responsible for teaching tens of thousands of people to understand and appreciate the wine. Of course, the question “is this a good wine or not” was one of the most important questions people wanted to get an answer for in such a course. Kevin’s explanation was very simple: “Take a sip of this wine. If this wine gives you pleasure, it is a good wine”. You can look at it as overly simplistic, as there are many factors affecting the perceived taste of wine – where we are, who we are with, the label, the story behind the label, the temperature, the mood, yada, yada, yada. Of course this all matters. But still, for majority of the cases, we are looking for pleasure out of drinking the glass of wine – the way it smells, the way it tastes, with all the little discoveries we make as we let the wine open up and change in the glass (“ahh, I taste blueberries and chocolate now”) – all those little pleasant moments we experience with every sip, it gives us a pleasure of enjoying a glass of wine; if we are getting the pleasure, this is a good wine. Yep, I said it was simple.

Very often pleasure is simplistically associated with erotic and sex, or at least that would be the very first thing which will come to the mind of many once they hear the word “pleasure” – oh no, I see your condemning look, of course I’m not talking about you, you are wired differently. Meanwhile, we derive pleasure from everything which surrounds us, and from everything we do – and if we don’t, we work hard to fix it. Every waking moment of our day is a perfect illustration to this. If we start our day from a walk or maybe a meditation – it is a pleasure of being one on one with yourself, deep in your own thoughts. Think about the pleasure of hugging that morning cup of coffee or tea and smelling the aroma. We look at the watch on our hand – it doesn’t have to be the Rolex or Philippe Patek to be admired and to create a feeling of pleasure. We put on a shirt or a blouse, look in the mirror – and we are pleased with the way we look (okay, fine, we might not be – but again, then we get to work hard to fix it). After the day at work, we come home to be welcomed by a wagging tail and a scream “mommy is home” followed by a huge smile and a hug – tell me that this is not what defines pleasure. No, not everything we do gives us pleasure – but those little bits and pieces of pleasure are what we seek, every time, every day.

Wine is simply a complementing part of our lives. Today we are in the mood for the white shirt, tomorrow – for the blue with yellow stripes; similarly, today you might want the glass of Pinot Noir, tomorrow it can be Tempranillo. We are constantly changing, and so do the things which we will get the pleasure from. People go from carnivores to vegetarians to vegans and back to carnivores – as long as we find pleasure in the way we are at the moment, that is all that matters. No matter what is in your glass, if it gives you pleasure, it is a good wine. It really doesn’t matter what the experts said about the wine you are drinking. It really doesn’t matter what your friends say. If this is White Zinfandel in your glass, and it gives you pleasure, it is a good wine. If this is massive, brooding Barolo, and it gives you pleasure, it is a good wine. If this is big, oaky, buttery California Chardonnay, and it gives you pleasure, this is a good wine – don’t let anyone who says that Chardonnay should be unoaked and acidic to persuade you otherwise. It is okay to have your own, individual taste – we do it with everything else, and wine shouldn’t be any different.

If the wine gives you pleasure, it is a good wine.

This post is an entry for the 24th Monthly Wine Writing Challenge (#MWWC24), with the theme of “Pleasure”. Previous themes in the order of appearance were: Transportation, Trouble, Possession, Oops, Feast, Mystery, Devotion, Luck, Fear, Value, Friend, Local, Serendipity, Tradition, Success, Finish, Epiphany, Crisis, Choice, Variety, Pairing, Second Chance, New.

A Puzzle of a Hundred Pieces

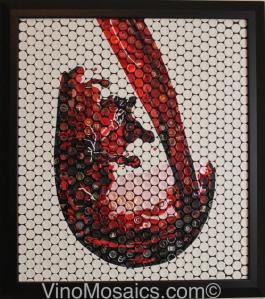

This beautiful artwork is constructed from tops of wine foils. Picture courtesy of Ryan Sorrell of VinoMosaic.com

Is there a person in this world who doesn’t like puzzles? You can save the “duh” exclamation for later – I’m sure there are some people who don’t, but an absolute majority enjoys the puzzles of some sort, whether expressed in the form of words, numbers, colorful picture pieces, link chains or whatever else.

So what if I tell you that you will be given a hundred of random pieces – not just you, but a group of people will receive a hundred of totally random pieces, but they all would have to build exactly one and the same picture out of those 100 random pieces – would you like to take part in such a challenge? Do you think you would be up for it?

While you still considering if you are up for a challenge, you are probably also wondering how puzzles relate to the wine and what you are still doing reading this nonsense where you were looking for the information on the wine, plain and simple. Actually, it appears that this type of puzzle with random pieces but the same resulting picture has very direct relationship with the world of wine. Not necessarily with the whole of it, but definitely with one of the most noble parts – the Champagne.

If you ever read the story of Benedictine monk Dom Perignon, often credited with creation of Champagne (”come quickly, I am drinking the stars”), many wine historians agree that major Dom Perignon achievement is not creation of Champagne itself, but perfection of the art of blending. If you think about it, blending resembles the process of putting together puzzle pieces. And to complete the picture, take a look at the description of any of the Champagne made by so called Champagne Houses – Veuve Clicquot, Moèt and Chandon, Bollinger, Perrie-Jouiet and hundreds of others – they all talk about a “signature taste” of their Champagne House, which is painstaking maintained exactly the same through the hundreds of vintages.

While I knew about significance of blending in production of Champagne, I never understood a true scale of an effort. A month ago (almost two month by the time I was able to finish this writing), I was lucky enough to attend a first ever Vins Clairs (give a few seconds – I will explain what this is) tasting hosted by the Champagne House of Piper-Heidsieck and Terlato Imports in the US – well, it was simply first ever Vins Clairs tasting conducted outside of France. The event was led by Régis Camus, Chef de Cave and Winemaker for Piper-Heidsick. And yes, we spent time learning about puzzles.

Let me give you a brief photo report for what was happening at the event first, and then of course we will go back to puzzles. When I arrived (early, to get a seat in front), the room was ready for the tasting:

And the expectations started building as the carts showed up:

And the expectations started building as the carts showed up:

This is what went into our tasting glasses:

This is what went into our tasting glasses:

Bill Terlato welcomed everyone to the tasting:

And then we started to learn about puzzle pieces. Of course, first talked about what Champagne is – “Champagne comes only from Champagne”:

And then we started to learn about puzzle pieces. Of course, first talked about what Champagne is – “Champagne comes only from Champagne”:

All grapes used in production of Champagne come from 320 different vineyards, which are also called CRUs. Out of those 320, only 17 have a status of Grand Crus – as they produce distinctly better grapes. Just to give you few more fun numbers – there are about 19,000 grape growers in Champagne, out of which only about 2,100 produce their own wine. There are also about 50,000 Champagne labels – which, of course, explains that it is always possible to come across a champagne bottle you never saw before.

All grapes used in production of Champagne come from 320 different vineyards, which are also called CRUs. Out of those 320, only 17 have a status of Grand Crus – as they produce distinctly better grapes. Just to give you few more fun numbers – there are about 19,000 grape growers in Champagne, out of which only about 2,100 produce their own wine. There are also about 50,000 Champagne labels – which, of course, explains that it is always possible to come across a champagne bottle you never saw before.

But let’s get to our puzzle, as we still need to solve it. Every year, the grapes are harvested (just a quick reminder – there are 7 grapes allowed to be used in Champagne, but only 3 – Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier are really used), pressed and fermented into the still wine, same as it would be done with any other wines – with the exception of color – red grapes, such as Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier, still produce clear juice if not kept in contact with skins, and this is what typically done in production of Champagne – unless Rosé is in the making. Once fermented, these still wines now become foundation of Champagne, known as Vins Clairs.

As common with any still wines, the year is a year is a year – every year is unique and different. If the year was great, let’s say, for Chardonnay, the Chardonnay Vins Clairs will become a Reserve wine and will rightfully occupy the place in the cellar. If the year was just okay, the wine, of course, will be used, but will not be cellared for long. If the year was terrible, the wine simply might not be produced. But it is okay – remember, we got lots of pieces to play with.

First, we tasted through 5 different Vins Clairs – each one a component in the Piper-Heidsieck Champagne, each one with its own role. Chardonnay brings fruit aroma, citrus, minerality. In reserve wines, Chardonnay will bring more aromas. Pinot Noir provides body and structure, and it is usually main component in Piper-Heidsieck Non-Vintage Champagne. Pinot Meunier brings fresh fruit. Below are my notes, almost verbatim, as I followed explanations and tasted the wines:

2014 Chardonnay Avize – Avize village is in the center of Côtes de Blanc, and it is one of the 17 Grand Crus. Straw pale color. Beautiful nose, minerality, fresh, citrus. Clean acidity on the palate, green apple, nice acidic finish. This wine was mostly used for vintage and reserve wines, and will be a part of non-vintage champagne in 5–6 years down the road.

2014 Pinot Noir Verzy – Verzy is also one of the 17 Grand Crus. Light golden color. Interesting nose, mostly white fruit, very serious acidity, lemon/lime level, very interesting. I would have to agree on structure. In a blind tasting I would say Muscadet.

2014 Pinot Meunier Ecueil (fleshy and fruity, red grape with white juice). Light golden color. Brings in fresh fruit to the blend. White fruit on the nose. Pinot Meunier rarely used for reserve wines. Still acidity, but acidity of the fruit, more of the green apples.

2009 Chardonnay Avize very interesting color – green into golden. Beautiful minerality, classic Chablis gunflint. Delicious. Creamy, medium body, white fruit, restrained acidity, long finish. I would gladly drink this wine by itself.

2008 Pinot Noir Verzy color similar to Chardonnay – green-golden. White fruit on the nose with touch of minerality. A bit more fruit on the palate, but still extremely pronounced acidity.

After we tasted through the 5 Vins Clairs, we were asked to refresh our palates with a sip of Pinot Meunier, and the final wine #6 was poured. Boy, what difference was that – mind boggling, starting from the color:

2014 Assemblage Piper-Heidsieck – blend of 2014 (90%) and reserve wines (10%) – darkest color of all, beautiful nose with yeastiness, and fresh bread, good minerality. One would never guess that you can get that from individual wines. Color came from the fact that the wine was not stabilized yet. Delicious overall, excellent acidity. 55% Pinot Noir, 15% Chardonnay, the rest is Pinot Meunière. There are 100–110 crus in this final assemblage, and the work on it was finished very recently. This wine was bottled in 2015, and will be released in 2018.

Someone asked if it is possible that the puzzle will not be solved in some years. Régis Camus gave us a little smirk, and said that no, this is not possible – the puzzle will be always solved.

What can I tell you? This was definitely an eye-opening experience – we were allowed to touch the magic, the magic of creation of one of the most revered wines in the world, and it definitely exceeded my expectations.

This was the end of the Vins Clairs tasting, but the beginning of “no-holds-barred” Piper-Heidsieck Champagne tasting -we had an opportunity to try all the major Champagne Piper-Heidsieck offers – 2006 Brut Vintage, 2002 Rare Millesime, Rosé Sauvage and Cuvée Sublime (Demi-Sec)

At this point, I was part exhausted, part excited, and stopped taking notes – I can only tell you that 2006 Brut and Rosé Sauvage were two of my favorites, but I would have to leave it only at that.

Here you go, my friends – the magic of Champagne, a puzzle of a hundred pieces – but the puzzle which is always solved. The New Year is almost here, and of course it calls for a perfect bottle of Champagne – but even if not a New Year, we can simply celebrate life, and every day is a good day for that. Pour yourself a glass of sparkles and let’s drink to the magic, and life. Cheers!

Oversold and Underappreciated Premise of Wine Pairing

This post is an entry for the 21st Monthly Wine Writing Challenge (#MWWC21), with the theme of “Pairing”. Previous themes in the order of appearance were: Transportation, Trouble, Possession, Oops, Feast, Mystery, Devotion, Luck, Fear, Value, Friend, Local, Serendipity, Tradition, Success, Finish, Epiphany, Crisis, Choice, Variety.

This post is an entry for the 21st Monthly Wine Writing Challenge (#MWWC21), with the theme of “Pairing”. Previous themes in the order of appearance were: Transportation, Trouble, Possession, Oops, Feast, Mystery, Devotion, Luck, Fear, Value, Friend, Local, Serendipity, Tradition, Success, Finish, Epiphany, Crisis, Choice, Variety.

Let’s start from the mini quiz – is food and wine pairing an art or a science? Or is it neither and the question makes no sense?

I’m sure you can successfully argue both sides, as they do in debate competitions. Technically, cooking process is based on science – heat conduction, protein’s reaction to heat and cold, combining acid and alkaline – we can go on and on, of course the scientific approach to the food and then the pairing can be argued very well. But one and the same dish can be flawlessly composed from the scientific point of view – think about a steak which is perfectly cooked with a beautiful crust – but missing on all the seasoning and having either none or way too much salt – it would require an artistry and magic of the Chef to make it a wow food experience. So may be food and wine pairing is an art after all?

I don’t have an answer, and I don’t believe it is even important. The problem is that in many cases, that “food and wine pairing”, which is typically sought out and praised, is not possible, not universal and even not needed.

Yes, there are rules for the pairing of wine and food. Contrast, complement, balance of the body of the wine with the perception of the “weight” of the food, tannins and fat and so on. The rules work well when you create a tasting menu and pair each dish individually with the very specific wine, based on practical trial and error. However, once you try to extend your recommendation to say “try this stew with some Syrah wine”, that begs only one question – really? And overbearing Shiraz from Australia, or earthy, spicy and tremendously restrained Côte-Rôtie or espresso loaded Syrah from Santa Ynez Valley – which one?

Here is another example, simply a personal one. At a restaurant, my first food preference is seafood – scallops, bouillabaisse, fish – anything. My wife typically prefers meat, and so do many of our friends. Going by the standard rules (white with fish etc.), we are either stuck with water or have to order wine by the glass, and ordering wine by the glass is typically not something I enjoy doing – very often, “by the glass” list is short, boring and grossly overpriced. So instead of trying to pair wine with the food (don’t get me wrong – I like the “spot-on” pairing as much as any other foodie and oenophile), I prefer to pair the wine with the moment – a good bottle of wine which doesn’t match the food is still a lot better than crappy wine which would denigrate the experience.

Still not convinced? Think about a simple situation – old friends are coming for a visit, and you know that these friends like wine. Yes, I’m sure you will give some thought to the food, however, there is a good chance that you will comb your cellar over and over again in a search of the wines to create the meaningful wine program for the evening, even if the whole dinner would consist of one dish. You will spend time and time again thinking about your friends and trying to come up with a perfect, special, moment-appropriate and moment-enhancing wines.

Wine is an emotional connector. Wine elevates our experiences, making them a lot more memorable. You might have problem remembering what dish you had at a restaurant, but if the bottle of wine made you say “wow” on the first sip, there is a good chance that the special moment will stay in your memory, thanks to that special pairing which took place.

We pair wine with moments, and we pair wine with the people, for good and bad of it. If Aunt Mary comes for a visit, who enjoys a glass of Chardonnay with a cube of ice in it, is it really the time to break out Peter Michael or Gaja Rossj Bass? A Bogle Chardonnay would pair perfectly with Aunt Mary (not that there is anything wrong with Bogle – it is just perfectly priced for such occasions). However, if you know that your friend Jeff will stop by, who you know as a Pinot Noir aficionado, all the best Pinot Noir in your cellar will all of a sudden enter into a “chose me, I’m better” competition. And if none of them will win, the Pinot Noir at near by store will enter the fray. And keep in mind, all of this will be happening whether you will be serving steak, salmon or cheese and crackers…

Yes, when food is well paired with wine, it is really a special experience. But food and wine pairing which doesn’t work is really not the end of the world, it is still just a nuisance – and a learning experience, if you will. When the wine pairs well with the moments and the people, that’s when the memories are created, and that, as MasterCard likes to teach us, is priceless. Let’s drink to lots of special moments in our lives. Cheers!

Of Wine And Balance

When assessing the wine, there are many characteristics which are important. The color, the intensity and the type of the aromas on the nose, the bouquet, body and flavors on the palate, the finish. When I’m saying “important”, I don’t mean it in the form of the fancy review with “uberflowers”, “dimpleberries” and “aromas of the 5 days old steak”. All the characteristics are important for the wine drinker thyself, as they help to enhance the pleasure drinking of the wine.

When assessing the wine, there are many characteristics which are important. The color, the intensity and the type of the aromas on the nose, the bouquet, body and flavors on the palate, the finish. When I’m saying “important”, I don’t mean it in the form of the fancy review with “uberflowers”, “dimpleberries” and “aromas of the 5 days old steak”. All the characteristics are important for the wine drinker thyself, as they help to enhance the pleasure drinking of the wine.

One of the most important wine characteristics for me is balance. Well, I’m sure not only for me, otherwise the organizations such as IPOB (In Pursuit Of Balance) wouldn’t even exist. Of course as everything else around wine, the concept of the balance is highly personable – or is it? What makes the wines balanced? What does it even mean when we say that “the wine is balanced”? This is the big question, and I don’t mean to ponder at it at a great depth, as this is a purposefully a short post. But nevertheless, let’s just take a quick stub at it, shall we?

In my own definition, the wine is balanced when all the taste components are, well, in balance. Okay, don’t beat me up – we can replace the word “balance” with the word “harmony”. In a typical glass of a red wine, you will find acidity, fruit and tannins (which is mostly a perceived tactile sensation in the form of drying feeling in your mouth). You will also often find other flavors such as barnyard, toasted oak or burning matches, which are typically imparted by the vineyard’s soil and/or a winemaking process, choice of yeast, type of aging and so on. But – in the balanced wine, nothing should stand out – you don’t want to taste only fruit, only tannins or only acidity – you want all the components to be in harmony, you want them to be complementing each other, enhancing the pleasure you derive from drinking of the wine.

And then you got an alcohol. On one side, I should’ve listed the alcohol above, as one of the components of the taste – alcohol often can be associated with the perceived “weight” of the wine in your mouth, which we usually call a “body”. Alcohol can be also related to the so called “structure”. But the reason I want to single out an alcohol is because way too often, we tend to use it to set our expectations of the balance we will find in the glass of wine, as this is the only objective, measured descriptor listed on the bottle. You might not taste the “raspberries and chocolate” as the back label was promising, but if it says that the wine has 14.5% “Alcohol by Volume” (ABV), this would be usually very close to the truth. Of course there is a correlation in the perceived balance and the alcohol in the wine – if you taste alcohol in direct form when you drink wine, it will render the wine sharp, bitter and clearly, unbalanced. But – and this is a big but – can we actually use the ABV as an indicator of balance, or is it more complicated than that?

When IPOB started, this was their premise – search for the wines with lower alcohol content (don’t know if it still is). Typical ABV in the old days was 13.9% (there were also tax implications of crossing that border). So should we automatically assume that any wine which boasts 14.5% ABV will not be balanced? I do have a problem with such approach. I had the wines at the 13.5% ABV, which were devoid of balance – including one from the very reputable Napa producer who will remain unnamed. And then there is Loring Pinot Noir, where ABV is dancing right under 15% (at 14.7% to 14.9%). Pushing envelope even further, you got Turley and Carlisle Zinfandels, where ABV is squarely stationed between 15% and 16% (occasionally exceeding even that level). Have you tasted Loring, Turley or Carlisle wines? How did you find them? To me, these wines are absolutely spectacular, with balance been a cornerstone of pleasure.

What prompted this post was the wine I had yesterday – 2007 Domaine de Saint Paul Cuvée Jumille Chateauneuf-du-Pape (95% Grenache, 5% Muscardin), which was absolutely delicious, and perfectly balanced, with round, smokey, chocolatey profile. The wine also had a touch of an interesting sweetness on the finish, which prompted me to look carefully at the label – and then my eyes stopped at 15% ABV, with the first thought was “this is amazing – I don’t find even a hint of the alcohol”. Judging by this ABV number alone, the “alcohol burn” would be well expected.

Yes, the notion of the balance is personal. Still – what makes the wine balanced? Can we say that some types of grapes, such as Grenache or Zinfandel, for instance, are better suited to harmoniously envelope higher alcohol levels? Is it all just in the craft, skill, mastery and magic of the winemaker? I don’t have the answers, I only have questions – but I promise to keep on digging. Cheers!